Aktywne Wpisy

Fennrir +270

O cie hooy, teraz się dowiedziałem jak wygląda nowa seria 7. Światła to chyba z Citroena Cactusa zaјebali xD

Gratulacje dla projektantów, przedliftowa E65 już nie jest najbrzydszą serią 7 jaka powstała

#bmw #samochody #motoryzacja ##!$%@? #grafikplakaljakprojektowal

Gratulacje dla projektantów, przedliftowa E65 już nie jest najbrzydszą serią 7 jaka powstała

#bmw #samochody #motoryzacja ##!$%@? #grafikplakaljakprojektowal

vulfpeck +270

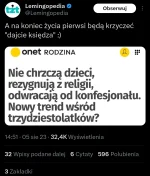

#bekazkatoli #urojeniaprawakoidalne #neuropa

Katole w odmętach szaleństwa i ostatnich podrygach konwulsji, próbują wyśmiewać trend, którego nie są w stanie powstrzymać.

Katole w odmętach szaleństwa i ostatnich podrygach konwulsji, próbują wyśmiewać trend, którego nie są w stanie powstrzymać.

Whitepaper o publicznym mieszkalnictwie w Singapurze + trochę wgląd w to jak wygląda singapurskie państwo dobrobytu ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

PDF

An exceptional public housing system

Housing is one of the most intractable policy challenges facing many countries and large cities. Where housing is in shortage, housing costs can quickly become a problem. For instance, across the European Union, a tenth of the population spend more than 40% of their disposable income on housing (Pitini, Ghekière, Dijol, & Kiss, 2015). This percentage of spending is even higher among poorer persons. Governments often respond by offering social housing at subsidised rents. These have led to concerns about poverty concentration and, where there is insufficient public investment, problems with basic housing quality and neighbourhood deterioration. In the post-crisis environment of fiscal austerity, pressures on public housing systems have grown and cities such as London now face acute housing shortages and long wait lists for social housing. When housing problems coincide with other forms of vulnerability,they may also result in homelessness and other forms of social exclusion.

Singapore’s public housing landscape offersa dramatic contrast. The sheer scale of the housing programme is remarkable. Some 80% of Singapore’s population live in flats built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB, 2016). At the same time,the mix of public and private is also distinctive. While planned, built, and allocated by the government, HDB flats are sold to the public on 99-year leases rather than rented, and thereafter may be traded on the resale housing market largely in the manner of private housing. In terms of policy design,the public housing system is unusual in that it also performs a range of secondary policy functions that are quite unrelated to housing. This article reviews the context of this exceptional approach to public housing, the complex policy goals and instruments it involves, and the emerging challenges.

Policy context

Public housing policy in Singapore reflects three considerations. The first is universal homeownership as an overarching policy principle. The public housing system inherited from the British colonial administration was not oriented towards ownership at the outset, but sought to deliver basic public housing at an affordable rent to as many people as possible in order to replace widespread slum dwellings. In the late 1960s there was a shift in policy direction towards selling public housing and, by the 1980s, homeownership rates were growing so steadily that the housing minister at the time declared a national goal of universal homeownership. Although that policy goal is no longer explicit, there remains a distinct policy preference for ownershipover social renting. Only 6% of the public housing stock caters for poorer households on a rental basis(HDB, 2016), performing the function of social housing in other countries. There is recognition that rental housing must continue to be available for the oldest and most vulnerable tenants who have little realistic opportunity of purchasing housing. But for younger households, renting is considered to be a stepping stone to ownership. Various schemes subsidise housing purchase or provide social interventions that are thought to address the behavioural factors behind social renting.

Second, the extensive coverage of purchased public housing must also be understood in relation to other social policies in the country. Social protection in Singapore remains fairly lean. There is no minimum wage protection, although a few occupations are now governed by regulations that stipulate wage increments alongside skills training. There is no unemployment insurance. Instead the general approach is that of workfare or work activation. Out-of-work persons may receive financial assistance by demonstrating effort to find work with the support of career advisors and social workers. Healthcare at the tertiary level is paid for through a mix of public subsidies, insurance, individual savings, and out-of-pocket payments. Formal education comes closest to universal provisionbut, even so, universalism only applies from age sevenonwardswhile pre-school education is left to private providers. In this context of minimal social protection, the availability of subsidised public housing becomes critical to maintaining social peace and meeting social needs, since it is often one of the largest items of expenditure. Public housing serves as a form of social wageto defray living costs and mitigatethe individual’s exposure to labour market uncertainties.

This social wage assumes even greater significance in old age, when work income starts to fall. At this stage, purchased public housing is an asset that can be converted into cash to meet income needs. Most old-age pension systems are built around the presumption of steady accumulation during working age followed by payouts in retirement. Singapore takes a different approach in that individuals are required to save at a very high rate but are also allowed to make large pre-retirement withdrawals, often leaving very little cash savings for retirement. Under the rules of the Central Provident Fund (CPF), which started out as a pension scheme in the 1950s, all workers make mandatory monthly contributions of up to a fifth of their wages while their employers contribute up to another 17% of wages. These contributions go into personal accounts that were originally meant to fund retirement spending. However from the 1960s, the rules were gradually relaxed to allow withdrawals for purchasing housing. This proved to be an extremely popular measure and the only practical way for many families to pay for housing, making the CPF in effect a housing saving scheme. Housing now accounts for the largest portion of annual CPF withdrawals, rather than retirement income (Ng, 2011). One of the fundamental principles governing housing policy is therefore that the equity in housing assets must be released in old age to compensate for low pension savings. These considerations are tightly intertwined. If social policy is designedon the understanding that homeownership will offer protection from social risks, including lower incomes in old age, then universalism in the sense of even and widespread access to public housing becomescritical. The next section will consider the policy instruments used to enact these principles

(...)

Conclusion

Singapore’s public housing system is remarkable in many ways. Observers are often struck by the scale of public housing, which accommodates four out of every five personsin Singapore. This reflects the overarching commitment to homeownership, which is better understood in the context of a social welfare system that prefers individual saving and asset-building over direct social spending and income redistribution. What may be less obvious are the ways in which housing policies have sought to harmonise a complex range of policy objectives that may not always be compatible or related to housing. There are unavoidable trade-offs, such as between affordability and quality. Income inequality will make this tension more apparent and require policymakers to stretch the range of housing options to meet diverse means and tastes. The public housing system has also been gearing up for the ageing population in a society where family forms are evolving. Economic changes that contribute to labour market insecurity will make basic services such as housing even more important, but also call into question the viability of Singapore’s homeownership model. For all these reasons, public housing is likely to be a domain of significant and continued innovation in the years to come

#neuropa #singapur #gospodarka #gruparatowaniapoziomu

@yeron: jezu komunis

I trochę wątpię by nas było na to stać.

I jeżeli chodzi o public housing to te domy powinny być raczej losowane, bo jeśli nie to na początku działania programu dostaną je najgorsze męty co pewnie źle odbije się na pr programu.

możliw

Trzeba też patrzeć, że ten program rozpoczął się w latach 50, a Singapur wygląda inaczej niż Polska jeśli chodzi o urbanizacje i gęstość zaludnienia.

Z drugiej strony u nas też funkcjonuje posiadanie mieszkania jako funkcja zabezpieczenia emerytalnego, ale tylko dla bogatszej części społeczeństwa.

W Singapurze Panie, które są pomocami domowymi mają prawnie zagwarantowany 1 dzień wolnego "dla siebie". W tym czasie pod żadnym pozorem nie mogą przebywać w miejscu pracy. A zatem spędzają go na mieście i to całkiem dosłownie, bo nie mają swoich mieszkań. Robią sobie takie całodobowe "pikniki", nocując w skleconych z kartonów tymczasowych obozowiskach.

To to sobie wymyśliłeś bo oczywiście nie ma takiego zakazu. Co do reszty to o wszystkim wiem, ale nie wiem jak to się ma do publicznego mieszkalnictwa Singapuru.